Sobre nós

Learn the real difference between press brakes and panel benders, how each machine works, and which bending solution fits your sheet metal production. Ideal for manufacturers of cabinets, enclosures, and metal panels.

Contactar-nos

Publicações recentes

Categorias

Siga-nos

Novo vídeo semanal

Short answer: both are core solutions for sheet metal bending, but they target different part families, production models, and technical trade-offs. This deep guide explains how each machine works, the fundamentals of press brake bending versus panel bending, practical performance differences, and how to choose the right tool for your shop.

Introduction — two approaches to bending of sheet metal

Bending of sheet metal is deceptively simple in concept — deform a flat blank into an angle or box — but the “how” determines labor, repeatability, and part cost. For decades, the brake press / press brake machine has been the backbone of fabrication shops worldwide. More recently, the panel bender (also called panel bending machine or automatic panel bender) has emerged as a complementary technology optimized for high-mix thin-sheet production of cabinets, enclosures and box-type parts.

This article compares the two from first principles: mechanics, tooling, operator skill, throughput, accuracy, material limits, automation readiness, and total cost of ownership.

What is a press brake and how it works?

Basic concept and major components

A travão de prensa is a forming machine that bends sheet metal by pressing it between a punch (upper tool) and a die (lower tool). Typical components include the ram (driven by hydraulic, mechanical, or servo drives), the bed with die, backgauges for positioning, and programmable CNC controls.

Bending modes — air bending, bottoming, coining

- Air bending: The punch presses the sheet into the die but does not fully seat it. Angle is controlled by ram depth; advantages are low tonnage and flexible tooling, but springback varies with material.

- Bottoming (V-bottom): Punch seats the sheet against the die, producing more consistent angles with higher force and less springback.

- Coining: Plastic deformation across the bend line to fully remove springback; high tonnage required and used for tight tolerance parts.

Tooling and operator role

Press brakes rely on matched tooling (punch/die sets) sized for bend radii and material thickness. Operators (or programmers) select tooling, set clearance, backgauges, and often perform trial bends and angle correction. This is why the role of what is a press brake operator is both skilled and influential to part quality — tooling selection, bending sequence, and compensation strategies matter.

For a deeper explanation of how folding blades and automatic sheet handling work, see our full guide on what is a panel bender.

Strengths and limits

Press brakes excel with a wide thickness range (thin to very thick plates), custom tooling for special profiles, and single-piece flexibility. They are especially suited for heavy structural components or where large bend forces are needed. Limitations include operator dependency, tooling changeover time, and lower throughput for multi-side box parts unless automated cells are integrated.

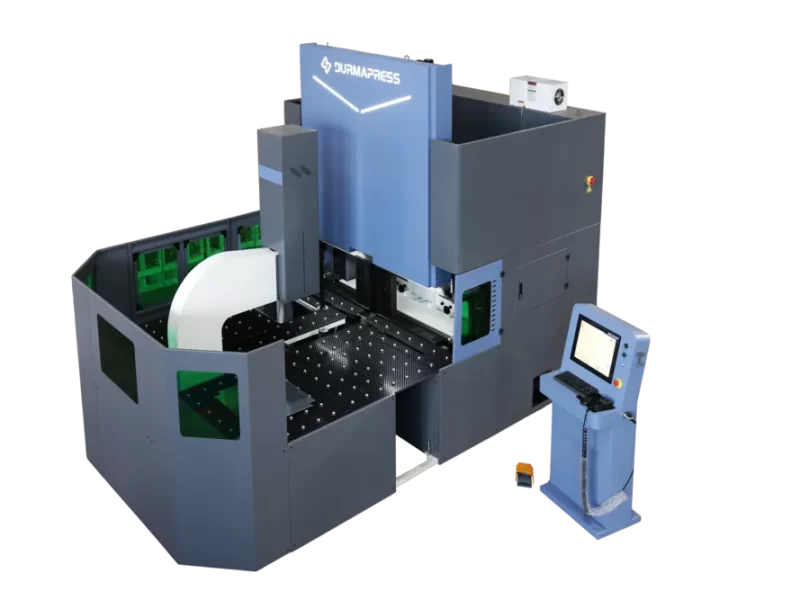

What is a panel bender and how it works?

Core mechanism and workflow

A dobrador de painéis is a CNC folding machine that achieves bends by clamping the sheet and moving folding blades (or beams) to wrap the metal around a clamping edge. Rather than a punch pressing into a die, the fold is generated by coordinated blade motion and often by rotating or repositioning the sheet automatically.

Automation and handling

Panel benders are commonly paired with automatic loaders, conveyors, and robots. The blank is clamped, multiple bends are executed by the folding beams, and negative/positive bends are achieved by automatic repositioning — often without manual flipping. This makes panel benders ideal for high-mix, thin-sheet, multi-side parts such as cabinets and enclosures.

Strengths and limits

Panel benders provide very high repeatability, fast cycle times for box-type parts, and near zero tooling changeover. They typically handle thin to medium thin gauges (common practical ranges around 0.5–2 mm for steel depending on machine model and material). They are not a replacement for heavy plate bending: material thickness and part size limits are design constraints.

Key technical differences (detailed comparison)

Bending method and material interaction

- Press brake: local plastic deformation from punch into die. Springback is compensated by operator/programmer or via higher tonnage (coining). Can handle thicker gauges.

- Panel bender: folding action with clamped edge and moving blades. Less tooling, different stress distribution, generally lower required tonnage for thin sheets.

Tooling & setup time

Press brakes require matched punch/die tooling and indexing for different profiles — setup can be significant for many SKUs. Panel benders minimize tooling changes: the same clamping and folding blades can produce multiple profiles, which cuts setup time and enables fast job changeover.

Operator skill and process variability

Press brake operation is skill-dependent: misalignment, incorrect backgauge settings, or improper tooling cause scrap. Panel benders reduce operator influence, relying instead on CNC programs and servo systems; consequently, shops see consistent part quality with less manual intervention.

Precision & repeatability

Panel benders often deliver higher repeatability for multi-side parts because the machine controls positioning and folding sequence precisely. Press brakes can be precise, especially with skilled operators and closed-loop systems, but repeatability across many operators or shifts can vary.

Throughput & automation readiness

A panel bender with automatic loading/unloading and robotic handling typically achieves higher throughput for boxed parts because it eliminates manual flipping and tooling swaps. Press brakes can be automated into cells but often need more peripheral tooling and part-handling solutions to match panel bender line speed.If your factory is moving toward lights-out automation, our automatic panel bender solutions provide real-world benchmarks and layout options.

Material thickness and part geometry

Press brakes are more versatile for thicker and large plates. Panel benders are optimized for thin to mid-thin gauges and for parts whose geometry favors folding around a clamped edge (cabinets, panels, drawers).

Cost structure and factory footprint

Press brakes vary widely—from manual bench brakes to high-tonnage hydraulic monsters—so initial investment can be modest or large. Panel benders and their robotic cells have higher upfront costs and a larger footprint but can reduce per-part labor and rework for appropriate part families.

Practical considerations — pressing and punching

While bending is the core function, many shops also perform pressing and punching operations as part of the panel workflow (hole punching, embossing, lancing). Press brakes are occasionally fitted with punch attachments for light pressing, but dedicated punching or turret punch presses are usually preferred. Mentioning pressing punch operations is relevant when designing a production line: consider integrated processes (cut→punch→bend) to minimize handling.

How to choose — decision framework

To pick between or combine equipment, evaluate these dimensions:

- Part mix & geometry: If most parts are boxed enclosures, panel bender first. If parts are heavy plates or require deep single bends, press brake first.

- Thickness range: Press brake for wide thickness coverage; panel bender for consistent thin-gauge work.

- Volume & changeover frequency: High-mix small batches favor panel bender automation; low-volume custom jobs still favor press brake flexibility.

- Labor skill & staffing: Limited skilled operators push you toward higher automation (panel bender).

- Floor space & capital: Balance upfront cost and floor area against long-term labor savings and throughput gains.

- Integration needs: If you plan conveyors, lasers, or robotic cells, design for seamless material flow between cutting, punching, and bending stations.

In many factories the optimal answer is both: use press brakes for heavy or bespoke items and panel benders to automate high-repeat thin-sheet production. They complement each other.

Real-world metrics to consider (what to measure)

When evaluating machines, request or measure:

- Cycle time per part (including loading/unloading).

- Setup/changeover time between jobs.

- Repeatability in degrees and length (±mm/°) across a production run.

- Maximum panel dimensions and maximum bendable thickness.

- Required floor footprint for automated cells.

- Energy and maintenance costs (servo vs hydraulic differences).

- Operator training time to reach target throughput.

These metrics make ROI calculations concrete when comparing a press brake machine against a panel bending machine.

Conclusion — no single “best” machine, only the right mix

Both press brakes and panel benders are indispensable in modern metalworking. A press brake is the flexible, high-force workhorse able to bend thick and custom parts; a panel bender is the automation champion for fast, repeatable production of thin-sheet boxes and enclosures. The correct strategy is to map your product portfolio, quantify volumes and tolerance needs, and then deploy the machine mix that minimizes total cost per part while meeting delivery and quality targets.

FAQ

It depends. For boxed, multi-side thin-sheet parts and high mix production, panel benders often win on throughput and consistency. For thick plates, one-off jobs, or profiles needing special tooling, press brakes remain essential.

Programming bends, selecting tooling, setting backgauges, running trial bends, and compensating for springback — a role that requires both training and experience.

Light pressing is possible, but heavy or repetitive punching is better done on dedicated presses; integrate processes for efficiency.

Through compensation in CNC programs, selecting bottoming or coining modes, or choosing different tooling and process parameters (all techniques common in press brake work).